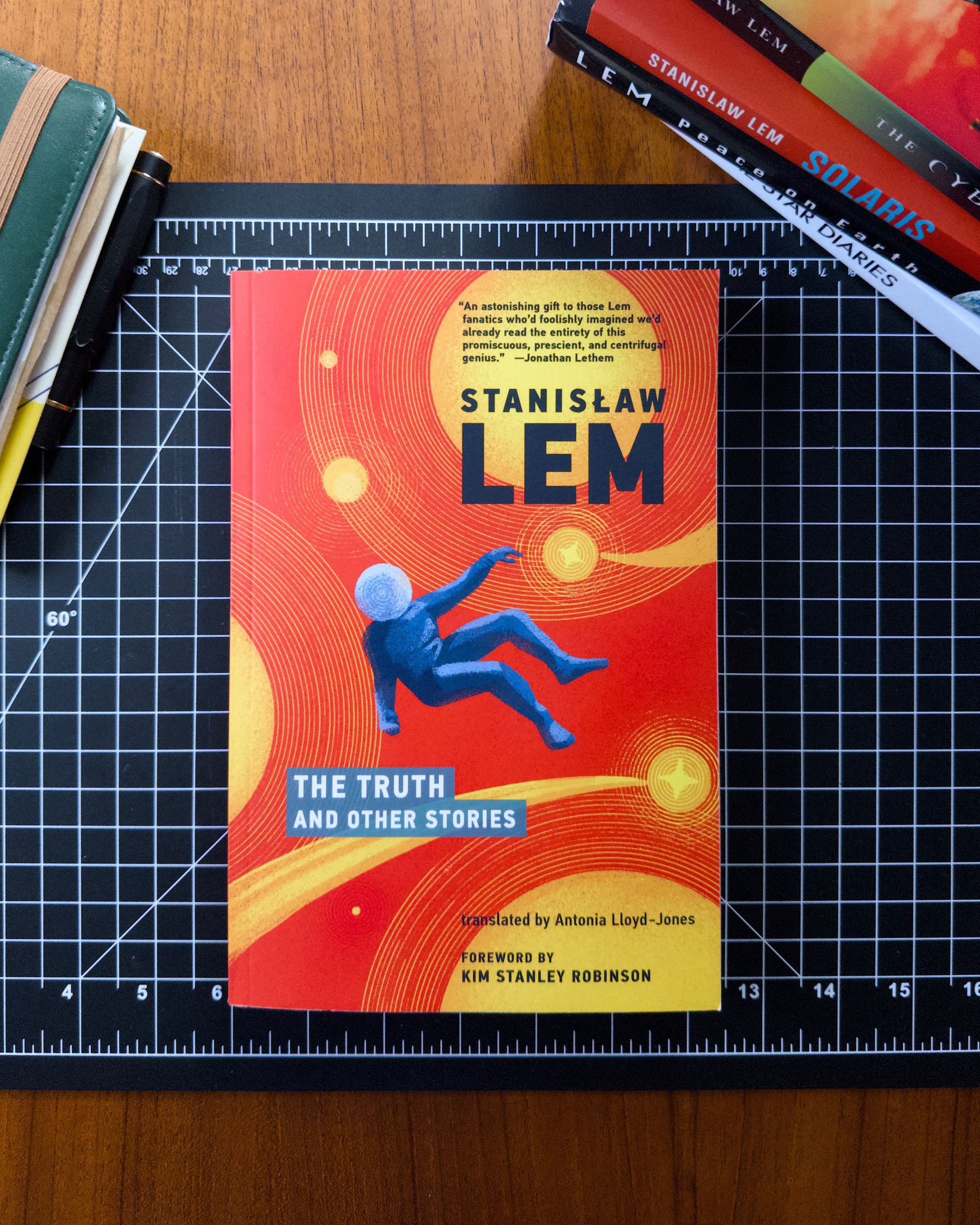

The Truth and Other Stories

A collection of inventive, fun stories, mainly penned from the late 1950s to early ‘60s. Many of these are less abstract or experimental than some of his later work and less psychological that Solaris but there’s plenty of absurdity going on with his typical genius for ludicrous but authoritative sounding scientific language, as well as masterful satirizing of bureaucratic and political systems, despite all the wild technology—some things never change.

I’ve always favoured Lem’s more satirical and philosophical side and there certainly is some of that here but on the whole these stories seem more akin to Anglophone SF stories of the 40s and 50s, not that I’m too familiar with that era but basically he was covering many of the same topics tackled in SF in the West previously.

These are not stories for those who prize character development above all. I love SF stories that are about ideas and Lem is great for that as Kim Stanley Robinson notes in his intro:

“It’s true, as Lem admitted in interviews, that his interest in humanity was general and not particular, so that he focused on the typical rather than the personal or pathological […] By using science fiction, Lem turned his natural interests and strengths into literary advantages. The philosophical problems that absorbed him were being illuminated in his time by ongoing work in the sciences, and these problems therefore had new permutations to explore during the years he was writing. In Lem’s work the forms matched the content, and he became an exemplar of science fiction in its purest state.”

And also: ”After the ordinary lineaments of fiction lost his interest, he was clever in the many ways he managed to express ideas in stories crushed to avant-garde experiments, reminiscent of writers like J. G. Ballard and Italo Calvino. These crushed stories allowed Lem to get his many ideas onto the page without being obliged to provide the stage business of dramatized scenes; they are science fiction not just in content but in form, being in essence abstracts of stories. The story in this collection called “The Journal” is a clear precursor of this kind of formal compression on Lem’s part.”